I recently read this and realized how comfortably, in comparison, we traveled around Kenya. But my post about public transportation is not going to be an exoticized adrenaline-filled white tourist narrative, “OMG it was crrrazy, so dangerous, but I did so well in there!” I know many urban sociologists (I even tried to become one) to put these experiences in perspective. What inspired me to write this was hearing from a European NGO worker who told us that her contract forbid her to use local transportation.

We always read public transportation as a system, and reactions or non-reactions that people show to various happenings can be too quickly generalized by travelers as what counts as normal. I keep remembering a story by an American fulbrighter – so unfortunate that she had two disgusting incidents in Vilnius twice in a short time. Also, I often think of Underground, a collection of true stories of Tokyo gas attack survivors, written up by Haruki Murakami, where he implies that some people could have been saved if they only talked to fellow passengers that something doesn′t feel right. In large cities, public transportation is an atomizing experience, for better or for worse.

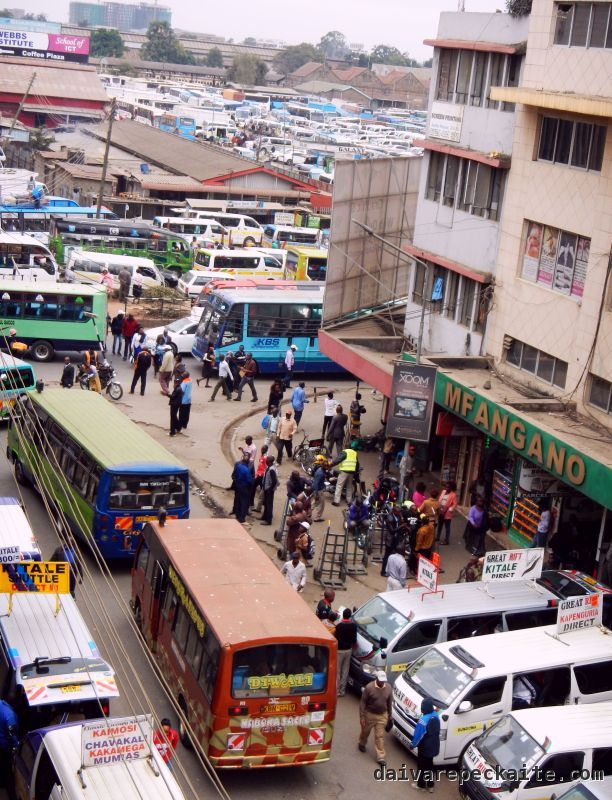

It took us some days and many questions to learn how the system works. It is not entirely correct to call city transport ‘public’, since municipal bus service is only a part of the system. Buses follow certain routes and congregate, like other forms of transport, in so-called ‘stages’, or stations – open-air local transport parking lots. In Mombasa, the second-largest city, local transport keeps circling its routes, so there is less congestion.

Private minivans, or matatus, are essentially the same as Eastern European marshrutkas or Israeli monit sherut. Even Lonely Planet warns about their careless driving and frequent accidents. When we were there, we heard about 16 passengers getting killed in a matatu in one single day. Also, my companion witnessed one minivan falling over from an overpass.

And yet, my companion and I agreed that we felt somewhat safer than in many other regions. The main difference between Eastern European marshrutkas or Israeli moniyot sherut and Kenyan matatus is that there are conductors in the latter, who make sure to notice and call (or catcall!) potential passengers, collect fees and remember who wants to get off where, so that drivers can solely focus on driving.

Traffic in large cities is almost as crazy as in Cairo, with endless jams and reckless drivers, but at least local transportation was available, frequent and quite reliable, with an exception of a day when there was a UN conference in Nairobi. While prices depend on time (more expensive during rush hours) and operator (some make their buses and matatus extremely elaborately fancy, with loud music, disco lights and drawings), we never experienced an attempt to charge a mzungu tax (= higher price for white people because they are expected to be rich and not to know local prices), unlike in markets.

I′ve sat in what Lonely Planet calls death seats and knew that if something was meant to happen, it can happen in any form of transportation. The dangers, I believe, mostly result in the poor quality of vehicles. It seems that everything is recycled in Kenya until it falls into pieces.

I will not lie that riding local transport was pleasant. Roads were often bumpy, vehicles were overcrowded, and it was difficult not to hit my head against the floor – and mind you, I′m anything but tall. Sometimes, while waiting for a bus to move in a never-ending traffic jam, the last thing I wanted was loud dance music. Once we were kicked out of a minivan in Mombasa because the driver wanted to take a large group in, and we were late for our appointment. We even saw a preacher getting on a bus and speaking for hours and hours, interspersing her monologue with frequent hallelujahs .

I wouldn′t normally take portrait photos of people on public transport, but preaching is a public act to get attention, so I treat her the same as I would if she was a campaigning politician.

For us preaching on the bus felt intrusive, but it seems that local people liked it and even donated money. Untypically, music was off. About a month after I returned from Kenya, I saw a preacher picking a passenger on a seat fenced from the exit by a glass barrier and overloading her with questions about spirituality. The Lithuanian preacher, however, worked on one target at a time. “Are you OK?” I asked the passenger, who was visibly annoyed. She shrugged, so I didn′t interfere.

Back to Kenya, it seems that Kenyan urbanites are very used to – and comfortable with – high levels of sensory stimulation on local transport. The intensity of these experiences made me remember taking public transportation in Japan. Everything was calm and quiet enough for people to sleep. People perpetually looked for strategies to make the most of their inevitably long commutes – if they could get a seat, they slept, and if not, they delved in their cellphones. In Nairobi, Mombasa or other cities of Kenya, sleeping on public transportation would require exceptional skills, but otherwise passenger etiquette resembled Tokyo rather than, say, Budapest, where people are chatting and making out everywhere. Locals in Kenya were often very curious about us, said hello and asked various questions on the streets, in markets or at the beach in Bamburi, but never on public transport. It seems to be an unwritten rule that commutes must be solitary.

Before my trip, I asked my only Kenyan friend at this time for tips, and he told me, half-jokingly, that matatus will be one of the best experiences of the trip. We did have some issues with unreliable online maps. Lack of schedules is compensated by the fact that during daylight hours buses and minivans run frequently. Most issues arise from urban planning (in Nairobi nearly all traffic has to go through a couple of main streets or the quality of vehicles. Like in Vilnius, some locals and officials must be contemplating a metro, but what a mess it would be to keep the city dug up for years…

Comments 2

Iam thinking about this question too.

And what about people culture, are they angry in rush hours?