Are multiple languages in public space an issue? Not in many countries. But in Lithuania there is an ongoing battle over some buses and street signs, which, in addition to Lithuanian, give translations in Polish. A law in Lithuania obliges all public signs (streets, institutions, etc.) to be in Lithuanian. The mainstream interpretation is that this implies they have to be in Lithuanian only.

I have already written (the editors sort of spiced up my text :)) about the controversy of names and public signs. As someone who has been to Novi Sad, where most institutions indicate their names in some six languages, I am surprised, to say the least, at how offended people feel about signs in Polish in the regions where the Polish minority is large or even dominant. Delfi, the most popular news portal, reports on an investigation which they started after a reader sent photos of signs in Polish. The municipality did not wish to explain why they have not been enforcing the law on one and the only language.

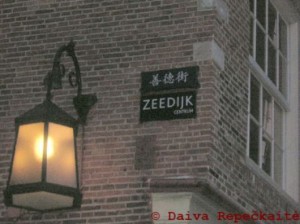

Meanwhile, bilingual signs are not a problem in Amsterdam’s Chinatown:

or in Israel, where the tension between the majority and minority is incomparable to that in Lithuania:

Needless to say, in the bilingual city of Brussels, where I am at the moment, all signs and announcements are in two languages, and sometimes English in addition to that. In Tokyo English accompanies all signs and announcements – otherwise foreigners would not understand them. One thing that is in common among all these countries is that they do not see it as a threat to either language. Brussels is a more French-speaking city in the Flemish-speaking part of the country. The omnipresence of English in Tokyo is mostly considered cool and desirable by the locals. In Israel you find Arabic on money, in the streets and so on – this is a minimum of inclusion. The difference is, Flemish and French are official languages of Belgium, Arabic is also one of the official languages in Israel, and so is Swedish (spoken by a minority slightly smaller than the Polish minority in Lithuania) in Finland. I would totally approve an amendment that in municipalities where ethnic minorities constitute at least 40%, their language should be one of the working languages of public institutions and present in the streets. Ethnic minorities in Lithuania have press and schools in their languages. It is rather difficult to see how street signs would suddenly be such a loss.

This is not to say that politically mobilised ethnic minority groups are by definition innocent. Predominantly Polish-speaking regions have become areas of politically stimulated tensions, pushy conservatism, and nationalism. Due to some manipulations, in some of these municipalities elections have been declared not free and fair, and had to be repeated. Mobilisation of ethnic sentiments among the poor and less educated parts of the populations in these areas leads to a monopoly of the Polish minority party, which would attribute it to themselves if bilingual signs were permitted. However, the insistence of the government on linguistic purism in the areas where minority languages are de facto working languages does not do anything to relieve these tensions.

Comments 1

As an Carinthian (Southern province of Austria) I have experience with bilingual streetsings. But here it was constitutional law, but nobody cared, they even moved the streetsigns so they don’t have to be changed due to a gap in the law. Finally they made it, now most signs are in Slovenian and German. Before they argued like idiots, now nobody cares anymore.